September Jobs Report: Happy Days Are Here Again

That is, IF the numbers are accurate and IF the Fed does not resume tightening the money supply. It's hard to have faith in these things.

The latest jobs report for the United States showed significantly better results than analysts had expected. Employers added 254,000 jobs in September, according to the Labor Department, well above the 150,000 increase The Wall Street Journal’s economic experts had predicted. Unemployment dropped by a tenth of a percentage point, to 4.1 percent

In addition, the July and August reports were revised upward by 72,000 jobs for the two months.

Happy days are here again, it seems. (I recommend the Jack Hylton version of the song.) The jobs report is very good news for U.S. workers—although we must remain cautious in our conclusions, because the Federal Reserve tends to get spooked by good news and respond by tightening the money supply or slowing the rate of an ongoing loosening.

September business surveys showed the service sector of the economy grew at a very good rate, with new orders and prices both rising. That is consistent with the Atlanta Fed’s estimate that the overall economic growth rate for the U.S. economy in the third quarter will be around 2 percent to 3 percent, as economist Robert Genetski notes in his Classical Principles newsletter. The manufacturing sector, which has been slow for the past year or so, also picked up, with big gains in the aircraft and defense sectors.

Rebuilding to repair damage by Hurricane Helene will increase the demand for labor, as will the defense sector manufacturing, Genetski notes. Oil prices were down by a very welcome 9 percent in September, which probably contributed to the rise in manufacturing orders, by easing production costs.

However, oil prices were up by 4 percent as of Friday, a bad sign. The rising war in the Mideast may stunt growth in the manufacturing sector and start to push up prices on both the producer and consumer levels again.

The quick settlement of the dock workers’ strike averts a potentially disastrous severing of supply chains, which would certainly drive up consumer costs and create massive shortages of food and other goods. The new agreement, however, will raise those labor costs, as port employers agreed to increase wages by 62 percent over the next six years—lower than the 77 percent the union was asking for, but still quite expansive and expensive.

The Biden administration “privately and publicly pressed the large shipping lines and cargo terminal operators who employ the longshore workers to make a new offer to the union,” as The Wall Street Journal reported, to avert a very embarrassing and impoverishing incident in the month before the presidential election. “Top White House and administration aides were in frequent contact with the employers,” the paper coyly notes.

The agreement is seen as a huge win for the union, as indeed it is. The workers’ base hourly pay will rise from $39 to $63 over the next six years. That will contribute to price inflation for the next several years. Stickers depicting a grinning Joe Biden pointing at the price tag on imported food and saying “I did this!” will be appropriate.

That is, if the deal continues for the full six years. Powerful evidence of the ending of the strike being a political agreement between the White House and the dock workers’ union is in the fact that the contract will expire in just three months, on January 15, 2025, well after the election and right before the next president is sworn into office.

The agreement removes a big potential impediment to the Democrats’ election chances for next month, but it leaves in place a potentially disastrous confrontation for early next year.

“The shipping lines, which reported record profits during the pandemic, will have to decide how much of the added costs to pass along to their customers, which are the big retailers, manufacturers and farmers that import and export through the East Coast and Gulf Coast ports,” the Wall Street Journal story notes.

My expectation is that they will pass on the great majority of the costs, and the retailers and others will dun their customers for it. Why would any of those parties do otherwise? An inevitable increase in overall price inflation will take care of the problem for them.

With all of this in mind, the Fed will probably feel constrained to go light on the next interest rate reduction, although the central bank already tamed the last Biden-Harris round of inflation last year and has held interest rates high since then solely because of a major flaw in its preferred inflation calculation, as I noted in last week’s issue, plus the fact that the Fed always makes its money supply moves too late, too sharply, and by too much and holds them for too long, as I have noted often.

It is significant that the Fed’s interest rate cut in September has not yet had any noticeable effect on consumers and small businesses, another Wall Street Journal story reports. Consumer confidence is declining, as is that of small-business owners:

Sentiment surveys already suggest that jitters are building. Last week a measure of consumer confidence suffered its biggest one-month decline in more than three years. And a recent survey of confidence among small-business owners fell more than expected in early September, keeping the gauge below its 50-year average for 32 consecutive months, according to the National Federation of Independent Business.

Investors evidently foresee trouble for everybody but the largest businesses. “Small caps were expected to see some relief from lower interest rates,” but they did not, the story reports, even though “about 36% of the debt held by companies in the Russell 2000, excluding financial firms, is floating-rate,” and therefore their loan costs should decrease as the benchmark interest rates decline.

“‘It’s profits that matter, and the profits are not being generated by the Russell 2000 companies,’ said Michael Rosen, managing partner and chief investment officer at Angeles Investments. ‘They’re being generated by these big megacap companies, and that’s why they’re the market leaders,’” the story goes on to say.

It is likely that the larger, better-capitalized “megacap” companies are much better-positioned than smaller firms to soften the impact of rising costs of fuel, labor, borrowing (interest rates), and other production inputs.

Investors’ caution about putting their money into small cap companies indicates that the prospects for those firms are not improving as hoped. “About 42% of the companies in the Russell 2000 are unprofitable, compared with 6% in the S&P 500, according to data from Torsten Slok, chief economist at Apollo,” the Journal reports.

This divergence of economic success is driving jobs out of smaller firms and into big companies, the Journal reports in another story:

The U.S. job market is still historically healthy, but less healthy than it’s been for much of the last several years. Fewer small firms have positions available, according to the latest monthly survey from the National Federation of Independent Business, due out later today. NFIB Chief Economist William Dunkelberg reports:

“In NFIB’s September survey, 34 percent (seasonally adjusted) of all owners reported job openings they could not fill in the current period, down 6 points from August and the lowest reading since January 2021. Thirty percent have openings for skilled workers (down 6 points) and 14 percent have openings for unskilled labor (down 1 point). Overall, the job market seems to be softening.”

The NFIB economist adds:

“Job openings were the highest in the construction, transportation, and

manufacturing sectors, and the lowest in the agriculture and finance sectors.

However, job openings in construction were down 7 points from last month with 53 percent having a job opening they can’t fill. Overall, the percent of firms with one or more job openings they can’t fill remains at exceptionally high levels. This indicates continued upward pressure on compensation and, ultimately, on inflation. As labor markets soften overall, small firms may find more success in filling open positions.”

Thus the current employment numbers are bad news for small businesses, which create most of the jobs in the United States.

Neither consumers nor small businesses are visibly benefiting from the Fed’s too-late and too-small September monetary loosening. The rate cuts arrived in time to stave off a measurable recession before the November election, a nice gift for Vice President Kamal Harris and other Democrat candidates for political offices, but that’s about all.

In short, Democrats and giant multinational corporations are continuing to do better than everybody else. That is no accident.

Just as the Biden-Harris administration has aggressively concentrated political power in the national government bureaucracy, forcibly removing it from the states, the people, and their elected representatives, the Biden-Harris program has concentrated economic power within the central government and a rapidly shrinking coterie of large crony corporations operating in lockstep with the feds. Biden and Harris have achieved the latter through massive government overspending and borrowing, severe tightening of already-abusive federal regulations, and ferocious attacks on all political opposition—which warn big companies of the consequences of failure to toe the line.

Despite all this damage, the U.S. economy is still ambling along, slowly but doggedly, living off the remains of a (dying) national culture of ordered liberty, self-reliance, individual initiative, and rewards for the creation of desired goods and services—the American Dream (also dying).

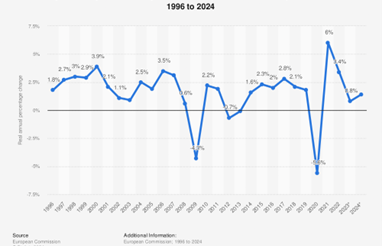

Russia did not have this when the Bolsheviks took over. China did not have it when the Communists took over in 1949. Cuba had some of this American influence when Castro took power, and it is still visible (tragically) in the old American automobiles still to be found there. Europe has increasingly cast aside the American economic culture in recent decades, and the EU economy has stagnated badly:

Annual economic growth of 2 or 3 percent is not bad, though it is not good, either. America can do better, and it has often done so, invariably when the federal government has lowered taxes and regulation and implemented sound money:

What we need today is the same thing as always: for the federal government to get out of the way.