‘Liberation’ from What?

Trump's tariff plan looks like a deliberate attempt to destroy the current global economic system and replace it with something better—and no one can predict what that would look like.

It seems to me that President Donald Trump must have something more in mind with his “Liberation Day” tariffs than just punishing other countries.

Moreover, given the major disruption the president’s tariff announcement created in just two days, that “something more” had better be very big and extremely important.

Trump regularly mentions several things in regard to tariffs and trade:

decades of trade deficits

fairness (Americans getting cheated)

subsidizing other countries

American workers losing out (deindustrialization)

fentanyl, human trafficking, and other crimes fostered by other nations

current account deficits and balance of trade

The United States has consistently run large trade deficits since the 1970s, and the shortfalls increased rapidly beginning in 1997:

Source: Macrotrends

The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis relates the traditional explanation for this:

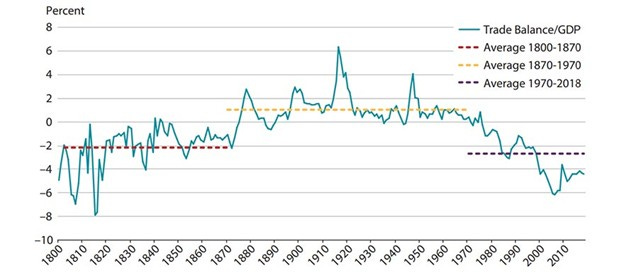

Figure 1: U.S. Goods Trade Balance to GDP

SOURCE: Bureau of Economic Analysis, World Trade Historical Database, Measuring Worth, and authors’ calculations.

Historically, industrialization has three phases: (i) the first industrial revolution features labor-intensive mass production, (ii) the second industrial revolution features capital-intensive mass production, and (iii) the welfare revolution features mass consumption in a financial services-oriented welfare state. We hypothesize that industrialization leads to structural changes that cause a nation’s comparative advantages to change relative to those of other nations. Since countries trade based on their comparative advantages, we would expect to see long-term changes to a country’s trade as it enters a new stage of development. Therefore, the long-term trends in Figure 1 can best be understood in the context of U.S. development.

There is no dispute regarding whether the United States deindustrialized during the past few decades. The Wall Street Journal supplied a chart demonstrating that:

Trump’s comments on tariffs and trade over the decades have valorized the economy depicted in the St. Louis Fed writers’ description of phase 2 of the industrialization/deindustrialization process. Trump’s tariff announcement on Thursday reflected that vision as well. The Wall Street Journal reports:

Trump leaned into that vision with his market-shaking tariff announcement Wednesday. “Empty, dead sites, factories that are falling down … will be knocked down, and they’re going to have brand new factories built in their place,” he said, to an audience that included members of the United Auto Workers union. “We’re going to be an entirely different country.” …

Trump’s aides see the tariff rollout as part of a comprehensive program, along with tighter borders, lower taxes and less regulation, that will result in a more self-sufficient economy, where Americans produce more and import less of what they consume, fewer jobs are filled by immigrants who came illegally, the private sector is freer and the government less burdensome.

In that economy, “We’re making a lot more stuff in America, high-tech manufacturing, security goods, autos, a lot more stuff across the industrial spectrum,” said Stephen Miran, chairman of Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers. Less regulation and taxes will “make it faster and more flexible to make stuff in America.”

Trump’s vision contradicts decades of general consensus on the effects of tariffs and on the evolution of national economies as exemplified in the St. Louis Fed essay. That raises the question of whether Trump’s vision of the economy is realistic or is a strange, personal quirk. The Wall Street Journal article entertains the possibility that it is the latter:

Trump’s rhetoric often evokes past eras when American manufacturing was at its zenith.

“As I was driving over, I see these empty old, beautiful steel mills and factories that are empty and falling down,” he told an interviewer in Chicago last year. “We’re going to bring the companies back.”

Princeton historian Julian Zelizer said Trump’s vision of the economy is fundamentally a nostalgic one. “It’s an older, manufacturing-based, 1950s-’60s auto-producing economy that I think he still envisions is possible, fueled by oil, not fueled by electricity.”

Former Republican Speaker of the House of Representatives Newt Gingrich, a supporter of Trump, disagreed. Trump, he said, admires Elon Musk and is enthralled by space travel. But he said Trump has returned the U.S. to its roots when it comes to tariffs and trade.

Trump, he said, is an admirer of President William McKinley, who raised tariffs sharply in the 1890s. “McKinley is simply the archetype of a pattern which began with [Alexander] Hamilton, who understood that if you didn’t have tariffs, British industry would drown you,” he said. Only since Franklin Roosevelt has free trade been “enshrined in modern economic thought,” he said.

In addition to this vision of a largely self-sufficient, highly productive country powered by cheap, abundant energy, Trump has spoken regularly about protecting the status of the U.S. dollar as the world’s reserve currency—the use of the dollar by other nations to trade with one another. That unique status makes the U.S. dollar highly sought-after around the world, which has major effects on the U.S. economy.

One of those effects is a sticking point for Trump. Many economists have argued that the reserve status of the U.S. dollar requires the United States to run current account deficits with other countries. As mentioned, nations around the world use dollars to make trades with one another, not just with the United States. That ensures consistency and reliability in the values of the items they are trading with each other.

That creates a momentous increase in the demand for dollars, which pushes up the value of the dollar versus other currencies—it makes the dollar “strong.” A strong currency, however, spurs current account deficits by making imports less expensive in the strong-currency country and the strong-currency country’s exports more expensive in other countries.

Thus, global demand for U.S. dollars as the world’s reserve currency forces other nations to run current-account surpluses vis-a-vis the United States. Note that this is not a truly free choice on their part: they have to receive more dollars than they spend, in order to accumulate dollars that they can use to trade effectively with other nations, and the simplest way to do that is to sell more to us than they buy from us.

To make sure that happens, these nations often deploy tariffs against U.S. goods, lest their businesses and consumer buy so many U.S. goods that their national stock of dollars dries up. Some nations also “dump” goods on the United States, taking a loss on them just to get more dollars.

It is not (necessarily) a matter of greed or malevolence in any particular case. It is just a fact of life. It is also clearly the source of Trump’s complaints about unfair trade, the United States getting ripped off by other nations, current account deficits, and the like.

Under this scenario, the real reason those countries have been imposing tariffs on U.S. goods is to ensure that they run current-account surpluses so that they can get enough dollars to cover their needs.

Some analysts argue that this process is what forced the United States to deindustrialize: foreign-made goods became cheaper than U.S.-produced ones. In this vision, deindustrialization is at least in part a result of the establishment of U.S. dollar at the center of the world’s currencies in the Bretton-Woods Agreement of 1944.

It may be a coincidence that the U.S. trade balance began to decline a couple of years later, and the multiple decades of U.S. deindustrialization may all be a natural process of economic evolution. However, it is instructive that the U.S. balance of payments remained positive until President Richard Nixon ended the international convertibility of the dollar to gold (the most stable store of value) in 1971, which led to the imposition of floating exchange rates in 1973, as the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank chart above shows.

Meanwhile, the percentage of U.S. workers in manufacturing declined steadily since the mid-1950s, as the Wall Street Journal chart above illustrates. Was this a purely natural process, or did the establishment of the dollar as the world’s de facto reserve currency set this in motion? Other developed countries also deindustrialized in those years, suggesting that the U.S. experience was not unique.

In addition, there were other possible ways to balance payments, which the United States and its trading partners did not pursue.

One obvious way for other nations to get dollars would be for the United States to invest more in enterprises in those countries. Americans could have invested in those nations’ industries and in building houses, highways, electrical grids, and other important properties and infrastructure in those countries.

That would have sent U.S. dollars to those countries, as investments, with the profits coming back in dollars, leaving those nations with a net inflow of much-desired U.S. dollars. All that U.S. investment would have improved the quality of life in those nations while providing profits for people in the United States and balancing our accounts.

In addition, Americans could have bought land in those countries. That would have provided those countries with dollars without having to sell us more goods than they buy from us.

Those things did not happen. A possible explanation is that comparative advantage prevented it: Americans found it more profitable to invest in domestic industries than in foreign enterprises and land. It is likely that this was indeed a factor.

Another likely factor is that those nations did not want the United States owning a large amount of property in their countries, just as Americans today are concerned about China buying up U.S. farmland and other properties.

In any case, the United States took what seemed a very simple course: just let it play out in (what appeared to be) a free market. The other nations eagerly agreed to sell more to us than they bought from us and pocket the excess dollars to use in trade with one another.

That, however, amounts to a very distorted global economy. Trump’s tariff plan appears to be designed specifically to remedy that by forcing a resolution of the balance of payments disparities that result from the use of the U.S. dollar as the world’s reserve currency. On first glance, Trump’s tariffs look arbitrary and unconnected to the tariffs other nations charge us, as The Wall Street Journal reports:

The White House laid out new tariffs on more than 200 countries in two main ways. For more than half, it imposed a flat reciprocal tariff of 10%. For the rest, it added an additional levy based on a basic formula.

In these instances, the Trump administration determined costs it said countries imposed by taking the amount of a nation’s 2024 goods-trade imbalance with the U.S., then dividing that by the value of the goods America imports from that nation.

“Several economists said that basing tariffs off of bilateral goods deficits is confusing and illogical,” the Journal reports. It certainly has proven confusing, as the stock market reaction illustrates.

Trump’s plan makes sense, however, if the real goal of these tariffs is to force the U.S. balance of payments back toward zero. This is in line with the idea of scaled tariffs outlined in the 2014 book Balanced Trade: Ending the Unbearable Cost of America’s Trade Deficits, by Jesse Richman, Howard Richman, and Raymond Richman.

That book, as described by the Contemplations on the Tree of Woe Substack (where I first learned of it), “challenges the orthodox theory that free trade is always beneficial and argues for an alternate policy they call balanced trade,” in the Contemplations writers’ words. Rejecting “the neoclassical consensus on tariffs and trade, the authors demonstrate that it does not, in the long run, benefit consumers in the nation that refuses to use tariffs, and they “argue that mercantlism isn’t abandoned because it doesn’t work, but because it works so well it becomes no longer necessary.” The Contemplations writer quotes the book as follows:

Many economists assume that mercantilism is just a developmental strategy —that it will eventually be abandoned by its practitioners once they develop… It is true that mercantilists eventually abandon mercantilism. Mercantilism becomes pointless once their trading partners are too poor to be able to buy more imports than exports or once trading partners refuse to cooperate.

But the fact that countries eventually give up mercantilism after destroying the economies of their trading partners is cold comfort to their trading partners. Spain never again was a world power, the Dutch never again led Europe in technology and trade, Britain is now a shadow of its former self, and the United States may never fully recover.

The authors deploy game theory to explain why countries refuse to reciprocate against other countries’ trade barriers despite their deleterious effects, which Contemplations explains quite clearly. The main point is that although the nation being subjected to trade barriers (in the present case the United States) benefits by some small amount, the country imposing the trade barriers (China and others, in the present case) benefits by a large multiple of that.

That makes perfect sense because Country 2 would not impose the barriers unless they worked. That is why mercantilism exists. Through this process, the free-trading nation continually loses and the mercantilist country continually wins. Over time, the free-trade nation slides into economic decline, as the Richmans’ examples quoted above demonstrate.

The writer then goes on to present the Richmans’ policy recommendation:

[T]hey propose their own solution: The scaled tariff. The Richmans explain their policy like this:

The Scaled Tariff is a single-country variable tariff whose rate rises as the trade deficit increases and falls as trade becomes more balanced. It is a tariff upon all the goods being imported by a trade deficit country from a trade surplus country. No particular product is protected; the Scaled Tariff simply changes the terms of trade between the two countries much as currency devaluation would change the terms of trade with all countries. By targeting countries with which the United States has a large trade deficit, the Scaled Tariff would efficiently, legally, and effectively balance trade. It would be applied to all imported goods from trade surplus countries that have had a sizable trade surplus with the United States over the most recent four economic quarters.

The tarrif rate would cause the revenue taken in by the duty upon imported goods from the particular country to equal 50 percent of the trade deficit (goods plus services) with that country.

The Richmans provide the following example:

In 2012 the United States imported $440 billion of goods and services from China, while China imported $112 billion of goods and services from the United States, creating a trade deficit of $298 billion. An initial tariff rate of 35 percent on $427 billion of imported goods from China would be designed to collect $149 billion (50 percent of $298 billion) in tariff revenue.

Now, let’s compare the Richmans’ approach to the Liberation Day tariff formula that Surowiecki called “extraordinary nonsense”. The Liberation Day tariff formula takes the US trade deficit with that country and dividing it by the value of the country's exports to the United States, then divides that value in half. For instance, if China had a trade deficit with the US of $298 billion, and exports of $427 billion, then 0.5 x $298 billion / $427 billion) ~ 35%.

Do you see? Trump’s Liberation Day tariffs are are calucalted with the exact same formula as the Richmans’ scaled tariffs.

This, then, appears to be what Trump’s plan is all about: to arrest this process and reverse it. (Trump’s trade order combines the Richmans’ recommendation with a mild version of another strategy, the National Strategic Tariff, the Contemplations writer notes: “The only difference is that Trump has also included a national strategic tariff of 10% as a baseline. Trump trade policy is simply Ian Fletcher’s Free Trade Doesn’t Work combined with the Richmans’ Balanced Trade!”)

The purpose of the scaled tariff is not to impose these taxes as punishment but to create a positive incentive system to balance trade, the Richmans write:

The Scaled Tariff is nearly immune to counter-tariffs. Any country that enacts a counter-tariff would be increasing the U.S. tariff on its products. Instead of starting a trade war, the Scaled Tariff would provide automatic responses that would end the trade war that is currently being conducted upon the United States by the mercantilist countries. In terms of the game of chicken example developed in chapter 7, the Scaled Tariff is equivalent to a policy that automatically responds to the competitor’s move with the identical move. In the face of such a policy, the response with highest payoffs for trading partners is to cooperate by reducing trade manipulations.

The Scaled Tariff specifically and exclusively targets countries which are running trade surpluses with the United States. Thus, it specifically creates incentives for these countries to take steps to shift their trade toward balance by stimulating their domestic economies, removing tariff and non-tariff barriers, ending currency manipulations, and so forth. It avoids targeting trade relations with countries that are not contributors to global current account imbalances.

The tariff plan in Trump’s executive order is designed to affect the U.S. balance of trade with each nation by accounting for all trade barriers, not just tariffs: “the goal is not to achieve ‘free trade’, it is to achieve balanced trade, therefore the method by which this is achieved is not ‘recriprocity of tariffs’ but reciprocity of trade flows,” as the Contemplations writer notes.

This is certainly an ambitious endeavor, though it has the great value of simplicity, and it is targeted directly at a larger purpose.

Possible scenarios indicate the scale of the plan. It is imaginable, for example, that Trump’s Liberation Tariffs would spur a worldwide recession or depression as a shortage of dollars in other countries suppressed international trade.

Alternatively, the tariffs could lead to the dollar being replaced as the world’s reserve currency. That would greatly increase global economic instability, but it is unlikely to happen: there is no other country with a big enough and stable enough economy, government, and military to provide a secure foundation for such a currency. A group of nations might emerge to propose one of their currencies for this role, but this seems unlikely to satisfy the need.

A more plausible scenario, in my view, is that the global economic system will stabilize after a time of confusion, if national governments leave it free to do so. That is the way things work when governments do not interfere.

It is possible that the stable state in such a case would involve less international trade as a percentage of the global economy, with nations relying more on their own output. (Note that that is exactly what The Wall Street Journal describes as Trump’s vision for the United States.) Competitive advantage would suggest that this will create a less-efficient world economy as nations forego purchases of goods from others that make them more efficiently.

With all this in mind, it is plausible to argue that Trump’s plan is designed to expand free trade and disincentivize trade barriers, that it is fashioned to increase world trade, not suppress it, just as Trump has regularly stated. The initial reaction, with dozens of nations contacting the president with offers to negotiate new trade arrangements, accords with that interpretation.

The current floating-rate currency system with no stable measure of value creates worldwide economic distortions by massively disturbing the price mechanism, the means by which comparative values and competitive advantages are discovered. What Trump’s tariff plan looks like is a gamble that what will follow a final destruction of the current massively manipulated and distorted global economic scheme will be better than that.

Didn’t someone say that DJT doesn’t read?