Fed's Pause Unlikely to Avert Recession

The Fed always keeps interest rates too high for too long, strangling production of goods and services.

Federal Reserve (Fed) Chair Jerome Powell on Wednesday announced the central bank will pause its program of increasing interest rates, which has been in place for a year in an effort to reduce inflation to a target rate of 2 percent (though it is not, in fact, a “target”).

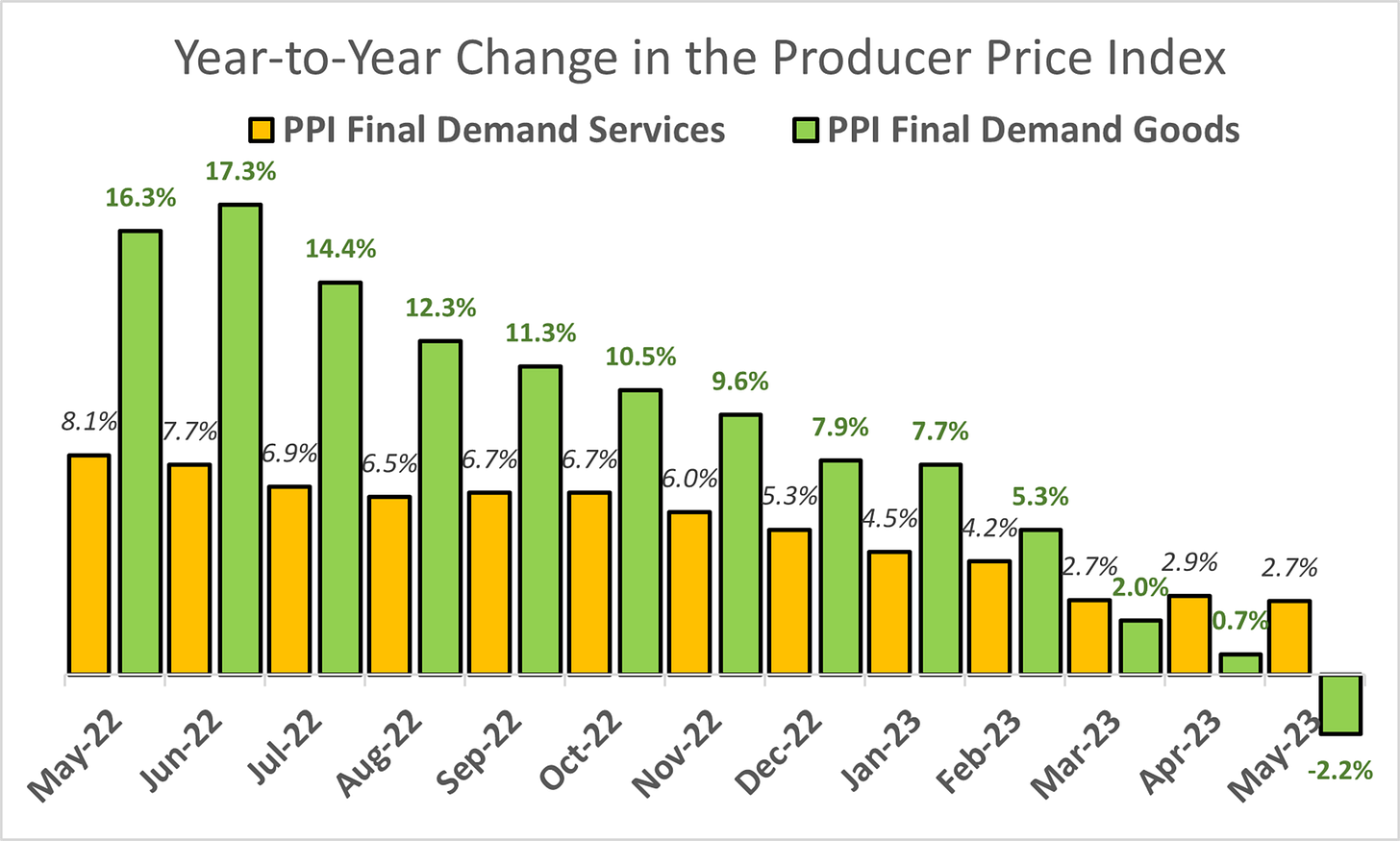

Inflation has slowed significantly and may in fact have already reversed, as Cato Institute Senior Fellow Alan Reynolds notes:

Suppose reporters once again hear the familiar grumbling about how ‘stubborn’ inflation is, and about how worried the Fed still is about the long, dark road ahead. I[f] so, couldn't some brave soul ask Chairman Powell to explain this sticky and stubborn (downward) trend of the Producer Price Index?

Powell and most other members of the Federal Open Market Committee remain convinced inflation is about to come roaring back and devour our purchasing power. As I’ve noted regularly for the past year, we should all be much more concerned about the Fed’s interest rate hikes crashing the economy. Unfortunately, the Fed adheres religiously to its false memory of “premature loosening” of the money supply having caused persistent inflation in the 1970s.

Speculation is that Powell’s use of the word “skip” to describe the Fed’s decision to refrain from hiking the Fed Funds Rate (and hence interest rates across the board) in June revealed a determination to resume raising interest rates next month. The Fed’s projections affirm that conclusion, The Wall Street Journal reports:

Powell’s phrasing during a press conference hinted that his default position for now is to raise rates at the Fed’s July 25-26 meeting, some said.

Fed officials’ new economic projections released Wednesday showed 12 of 18 expected to raise rates at least two more times this year to fight inflation, up from four officials in March.

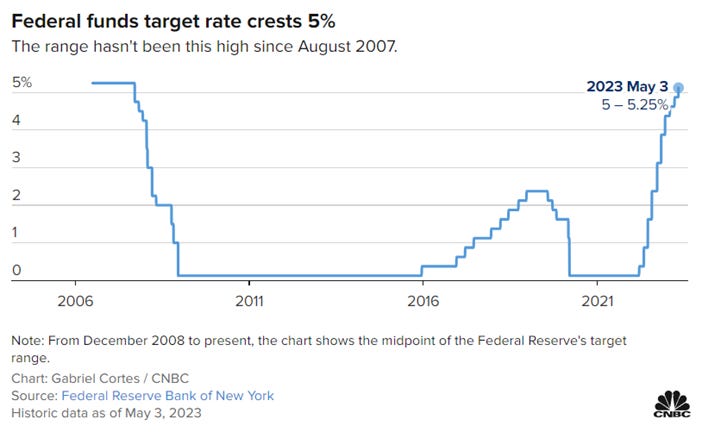

The Fed is holding steady at the highest target rate since 2007, which was followed by a historic liquidity crisis and recession, as this graph from CNBC illustrates:

Source: CNBC

The expected July increase would push the target interest rate to its highest point in 22 years.

Unfortunately, even that is not enough for the Fed. The Epoch Times reports:

The [Fed’s] Survey of Economic Projections (SEP) shows that officials anticipate the policy rate to rise to a median of 5.6 percent by the end of 2023. …

“The Fed caused heartburn with their estimates of future rates, implying their concern for high inflation outweighs the softening in growth we are experiencing,” Jeff Klingelhofer, co-head of investments at Thornburg Investment Management, said in a note. “The most concerning data point for markets is the significant rise in the ending target for the Federal Funds rate, which moved up a full 50 basis points to 5.6 [percent].”

Powell told the press the Fed will adhere to those high interest rates for another two years:

[S]ince we’re probably going to—we’re having real rates that are going to have to be meaningfully positive, and significantly so, for us to get inflation down, that probably means—that certainly means that it will be appropriate to cut rates at such time as inflation is coming down really significantly. And, again, we’re talking about a couple years out, I think.

As anyone can see, not a single person on the committee wrote down a rate cut this year, nor do I think it is at all likely to be appropriate, if you think about it. Inflation has not really moved down. It has not so far reacted much to our—to our existing rate hikes and so we’re going to have to keep at it.”

As I noted above, however, inflation has in fact “reacted much” to the rate hikes, and the latter are already damaging the economy, an effect which will increase regardless of what the Fed might do in the coming months. An additional two years of this would be absurd.

I believe that the Fed has already accomplished what monetary policy can do in taming inflation and that we are now simply awaiting the full effects of its rate hikes as the natural time lags for central bank monetary action come to pass.

Although the U.S. stock markets have been bullish lately, the data are showing increasing signs of weakness in the economy. The Fed’s goal has been to manage a “soft landing” from the recent bout of inflation, slowing excessive money growth without crashing the economy. Indications are that the Fed has failed to avert a downturn and has in fact created one—unnecessarily, as always.

Manufacturing has been slowing “notably,” Bloomberg reports: “Factory output barely rose in May, according to Fed data, suggesting manufacturers are growing cautious in the face of tepid global demand and equipment spending.”

Consumer spending is still growing, by contrast, The Wall Street Journal reports:

Consumers spent a seasonally adjusted 0.3% more in May at retail stores, restaurants and online, following April’s strong 0.4% advance, the Commerce Department said Thursday. That growth reflected robust hiring and rising wages that pumped up incomes in recent months, further defying recession predictions in early 2023.

“The recession will be delayed as long as consumers continue to spend,” Oren Klachkin, an economist at Oxford Economics, wrote in a note.

If consumers spend more while production of goods decreases, inflation could increase as consumer money chases supply-side shortages—unless people choose to move their purchases into services, which is what the consumer spending numbers are showing. In addition, a rise in imports of goods would also hold down inflation. Thus, the numbers do not indicate a resumed threat of inflation.

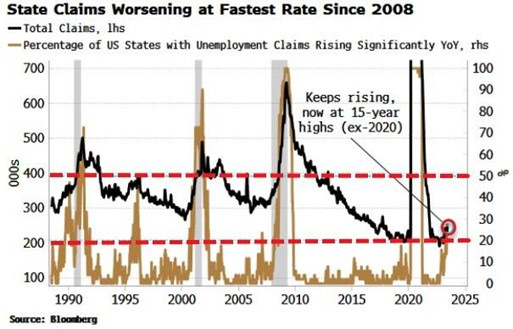

Recession is the real threat. Writing at ZeroHedge, Bloomberg macro strategist Simon White says recent economic data are sending an “ever stronger recessionary signal.” With unemployment claims rising in the nation as a whole, the number of states with worsening unemployment indicates the problem is widespread, which White plausibly says is a strong indicator that the economy is about to contract:

In this week’s data we saw another rise in unemployment claims to almost two-year highs. But it’s the underlying picture that’s sending the ever-stronger recessionary signal. The number of states with deteriorating claims continues to rise and is consistent with a near-term downturn.

Consumer spending is sending the same signal. The retail sales data for May, though still positive, show a downward trend that will intensify as it gets tougher for people to obtain credit, White observes:

The month-on-month figures beat or met expectations, but that should not distract from their clear downward trend. Moreover, trying to figure out what is going to happen has more utility than focusing on a short-term volatile figure. Tighter credit conditions posit that retail sales will continue to weaken through the rest of the year.

White argues that the evidence of an imminent economic downturn indicates that the Fed will not raise interest rates in July and will in fact cut the federal funds rate.

That would in fact be the wise course, and I have advocated it for months now. Unfortunately, I do not believe that the Fed will take that advice. What Powell said about keeping interest rates up for two more years is all too credible. The Fed always keeps interest rates too high for too long, until the resulting recession “squeezes the inflation out of the economy” by strangling production of goods and services and the employment that enables them and thereby reducing the effective demand for those things and thus the prices that people can and will pay.

That is a stupid and brutal way to manage things, but it is the Fed’s way.