Fed’s Interest Rate Hike Strengthens Stagflation Scenario

While everybody watches the Fed, the real problem is government spending.

The Federal Reserve (Fed) is taking another stab at taming inflation long after the conditions for inflation have largely ended and a recession appears more likely. Unfortunately, the Fed’s interest rate hikes are creating conditions for a return of inflation in addition to a recession.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell announced on Wednesday the central bank was raising interest rates by a quarter of a point, bringing the Fed Funds Rate to its highest point in 22 years. The target rate is now 5.25 percent to 5.5 percent:

Source: The Wall Street Journal

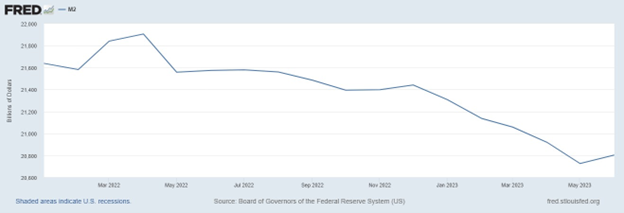

Raising interest rates slows the economy by making borrowing more costly, in addition to other effects. The Fed has been raising interest rates since March of last year (when rates were near zero), the most rapid sustained increase in four decades. The money supply has declined accordingly:

Source: St. Louis Fed

Upon announcing the latest rate increase, Powell said the central bank might push interest rates even higher and the Fed’s governors believe the ongoing monetary tightening will not lead to a recession.

The Fed continues to look at the unemployment rate as assurance that there will be no recession and that the real threat is still inflation. That is based on the Phillips Curve theory, which assumes low unemployment rates make workers too powerful and push up prices by increasing labor costs. The facts do not support belief in the Phillips Curve, however, as Cato Institute Senior Fellow Alan Reynolds notes:

[If the Phillips Curve were true,] the reduction of inflation since last June could not have happened. After 15 months in which the CPI inflation rate averaged 8.5 percent (and the fed funds rate was tiny), it has now fallen to 3.1 percent for 11 months. Did that happen because the unemployment rate went up? On the contrary, unemployment fell from 4.5 percent to 3.6 percent.

But the Fed and academic economists are not easily dissuaded by troublesome facts. They just keep on searching for new ways of explaining why the theory is still right, but the world has gone wrong.

A definite factor in the rise and fall of inflation over the past couple of years is federal fiscal policy, which has been absolutely harebrained. Hoover Institution economist John H. Cochrane explains how the federal government’s spending spree of the past few years fueled price inflation:

How do we get inflation from the big fiscal stimulus of 2020-2021, [a friend] asked? Well, I answer, people get a lot of government debt and money, which they don't think will be paid back via higher future taxes or lower future spending. They know inflation or default will happen sooner or later, so they try to get rid of the debt now while they can rather than save it. But all we can do collectively is to try to buy things, sending up the price level, until the debt is devalued to what we expect the government can and will pay.

OK, asked my friend, but that should send interest rates up, bond prices down, no? And interest rates stayed low throughout, until the Fed started raising them. I mumbled some excuse about interest rates never being very good at forecasting inflation, or something about risk premiums, but that's clearly unsatisfactory.

Of course, the answer is that interest rates do not need to move. The Fed controls the nominal interest rate. If the Fed keeps the short term nominal interest rate constant, then nominal yields of all bonds stay the same, while fiscal inflation washes away the value of debt.

As Cochrane observes, the money supply increased rapidly as the federal government pumped stimulus checks and other expensive boondoggles directly into the economy:

In March 2022, the Fed began raising the nominal interest rate to fight the inflation the federal government’s overspending was causing. The CPI began to turn the corner in late 2022, as the top graph above indicates.

The Fed has stubbornly implemented further interest rate increases since then, redoubling its efforts to increase unemployment in order to stop inflation. But the decrease in the money supply eliminates any need to push up unemployment even if you believe in the Phillips Curve. In fact, suppressing employment and overall economic output will fuel price inflation if the supply of goods and services decreases faster than the money supply.

The Fed’s interest rate hikes are now compounding the damage caused by the government’s overspending. Our fundamental economic problem is weakness on the supply side, which the interest rate hikes are designed to worsen. Domestic employment has stagnated, as economist Vance Ginn notes in The Daily Caller:

Turning to the latest jobs report for June, the figures are disappointing, falling well below expectations. Only 99,000 net jobs were added after accounting for downward revisions in the two prior months. Moreover, many of these jobs were government jobs, straining the productive private sector that pays for those jobs. According to the household survey, employment has remained nearly stagnant since March, indicating a lack of substantial job creation. To make matters worse, the labor force participation rate has yet to return to its pre-pandemic rate, indicating millions of Americans are uncertain about their job prospects.

In short, the economy is struggling—outside of government spending, which increases GDP far more than it raises the real supply of goods and services (if it does the latter at all, when you consider that the private sector would have used that money for things people want to buy). Continuing increases in federal spending—such as the debt ceiling deal and the Biden administration’s latest plan to forgive student loans—drain even more resources out of productive uses in the private sector for purposes of income redistribution.

As economist Robert Genetski notes at Heartland Daily News, the U.S. economy may already be weaker than most people think:

[W]e should be skeptical about the Atlanta Fed’s estimate of a 2 percent growth rate for the quarter now ending. Many economic estimates are based on soft numbers. One hard number estimate comes from the Treasury’s monthly report on tax receipts. With two-thirds of fiscal 2023 completed, the Treasury reports tax receipts down 11 percent from the previous year. Tax receipts are highly erratic and difficult to interpret. Nonetheless, these data through May point to a weaker economy than either the GDP or [Gross Domestic Income] would suggest.

A decrease in taxable income (and thus tax receipts) is particularly consequential in a time of continuously increasing government spending, as it makes the federal deficit even higher than expected. That raises the cost of the government’s interest payments, and the Fed’s interest rate hikes push them even higher, further draining resources from the productive private sector.

The most worrisome prospect for the U.S. economy at present is not low unemployment but instead the government’s ongoing suppression of the supply of goods and services produced domestically. That, plus excessive government spending, creates the conditions for inflation and slow or negative economic growth. When those conditions combine as they do today, stagflation is the dismal result.

It is hard to overstate how dire the government spending situation has become.