Critiquing the ‘New Conservatives’

Did liberty and market freedom really "hollow out" the American economy and destroy hardworking people's ability to live out the American Dream? Or was it something else?

With a large segment of the American right moving away from its traditional support for free markets, “It is essential to consider the arguments of policy scholars who are advocating for a shift to a conservatism that advocates for government intervention,” writes Civitas Outlook editor in chief Richard M. Reinsch III at Law & Liberty.

Reviewing The New Conservatives, a newly published book edited by Oren Cass, chief economist of American Compass and erstwhile domestic policy director for Mitt Romney’s 2012 presidential campaign, Reinsch notes the volume’s essays push for “greater government involvement in almost every policy area” and “argue we shouldn’t focus on the consumer but on the worker, especially workers engaged in the manufacturing sector.”

These self-described New Conservatives are simply pushing warmed-over pre-1960s progressivism with some pro-family spin, Reinsch argues.

“The book is decidedly protectionist, pro-industrial policy, pro-labor union, pro-family policy, and proposes a more robust alliance between Silicon Valley and the government,” writes Reinsch. “The message is clear: entitlements shouldn’t be cut, nor should current tax rates on any labor or activity be reduced. In fact, Cass has indicated that he favors increasing taxes on wealthy Americans” (emphasis in original).

Reinsch systematically examines the New Conservatives’ assumptions and policy proposals, quickly demolishing the movement’s focus on the worker over the consumer through the simple course of asking why anybody works:

Why do we work? We indeed find meaning and frustration in our work, fellowship, and rivalries, as well as opportunities and disappointments. But through all of that, we work to consume because we need to consume; that is, we must satisfy our needs and wants, and through work, we acquire the means to engage in exchanges with others. Economically speaking, that is the point of work. Would you continue to do your job if your wages were cut by 10 percent, 15 percent, or entirely? No. You’d look for other work.

The purpose of an economy is to meet the needs of consumers, since consumption is the ultimate reason why we work.

The New Conservatives’ false premise leads naturally to bad policy, whereas the consumer-oriented approach accords with human nature:

Conclusions follow this truth. One is that consumers don’t have the responsibility to keep certain workers employed. The producer must serve the consumer. Should we be required to buy things that are redundant or that we don’t need or want, to keep existing businesses alive? That is the absurd logic of Cass’s inversion of the consumption-production relationship. Moreover, feeding, housing, and clothing one’s family are essential expenses. How is making these consumption expenses more expensive pro-family?

After extensive criticism of Heritage Foundation President Kevin Roberts’ arguments in favor of greater government action, encapsulated by Roberts’ contemptuous dismissal of “the abstract economic pronouncements of some long-dead Austrian aristocrat”—meaning Friedrich von Hayek, “one of the foremost economic, institutional, and legal thinkers of the twentieth century,” in Reinsch’s accurate description—Reinsch turns to the specifics of the New Conservative complaints and checks them against the facts:

Did the working class meet its demise at the hands of free trade, NAFTA, and the WTO as Cass and Roberts insist? No. As AEI economist Michael Strain and investor Clifford Asness observe: “The wages of nonsupervisory workers—roughly the bottom 80 percent of workers by pay, including manufacturing workers and service-sector workers who are not managers—have grown by around 60 percent over the past two generations. Over the past three decades, inflation-adjusted wages for typical workers have grown by 44 percent.”

Strain and Asness cite a different finding on overall wealth accumulation, observing that data from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) notes that “families in the 51st to 90th percentiles of the wealth distribution had an average wealth of $1.3 million in 2022, the most recent year data are available. That’s up from around $500,000 in 1990, after adjusting for inflation.”

What about those with low incomes, Strain and Asness inquire? “The CBO’s income data show that inflation-adjusted post-tax-and-transfer income for the bottom 20 percent of households more than doubled from 1990 to 2021.” And “these families saw their average real wealth triple from 1990 to 2022.” Poverty rates have declined using the government’s official measure from above 20 percent in 1960 to 11 percent today. The standard is relative, so some poverty will always be found.

What about the boys down at the plant? Are we overlooking them?

In their famous paper describing the “China Shock,” David Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon Hanson observed a 13-year period from 1999 to 2011, concluding that imports from China resulted in a 21 percent decline in manufacturing employment, or a net loss of 2.4 million jobs. Numerous scholars have since questioned these findings of such job losses, reducing the number by half or even more. We should note the number of jobs created in America by imports, which economists also point to in evaluating China Shock.

Sympathy for those struggling through economic and social changes should not blind us to reality, and it is especially important not to ignore positive changes, Reinsch observes:

I don’t diminish job losses or the psychological toll they exert. It is a natural part of any freely functioning economy, however, and an inherent aspect of capitalism and America’s economic history. Six million jobs were also created during this same period in other sectors of the economy. Economist Jeremy Horpedahl has recently tested the jobs and incomes of the 10 cities most negatively affected by the China Shock. His findings indicate that most of them currently boast more jobs than they did in 2001. Moreover, these same cities have higher real wages for workers at every income level. Amidst the current push for reindustrializing America, we might wonder who will fill the already 450,000 open manufacturing jobs? Declinist narrative and DC opportunity mill meet economic reality.

Recognizing that new opportunities have arisen in place of old ways of doing things does not amount to callously telling people to “learn to code,” as the cliché has it. The U.S. economy has become more productive over the years, which is the only way to increase prosperity. The loss of jobs in the manufacturing sector is a result of a great increase in productivity, Reinsch writes:

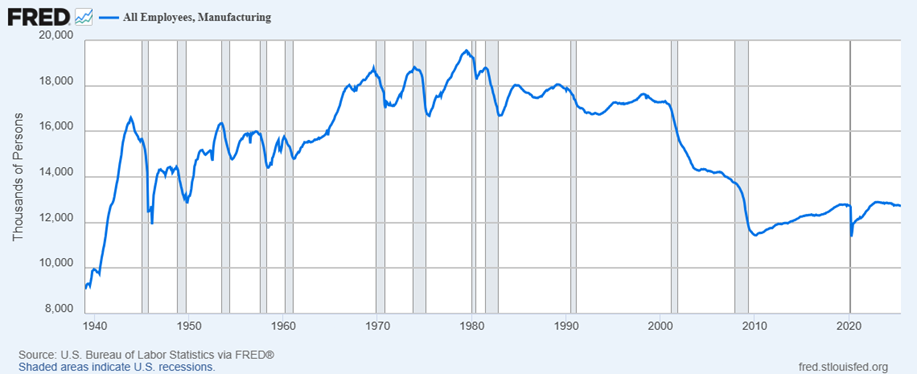

In meeting the needs of consumers, the American manufacturing sector has increased productivity since 1994, the year NAFTA was implemented, by between 70-80 percent. As George Mason University economist Don Boudreaux has noted in this space, “the productivity of American manufacturing workers steadily increased from the end of WWII until 2012; it neither stopped nor even slowed when America’s run of annual trade deficits started in 1976.” This productivity increase came at a time when this same sector began to shed jobs in earnest towards the end of the 1970s. This would be evidence of a robust sector, and yet virtually every Western country has watched its manufacturing sector decline during this period. America differs in that its manufacturing sector’s productivity is almost unmatched. Besides, as Harvard Kennedy School, NBER, and Peterson Institute economist Robert Lawrence has noted, productivity growth is the “dominant force behind the declining share of employment in manufacturing in the United States and other industrial economies.”

We can quibble with why manufacturing productivity has not continued to increase since 2012, but we might consider consumers again, who, as they grow richer and live in more prosperous economies, choose to devote fewer resources to manufacturing goods. America is now a service-based economy, and if we are going to speak the language of trade deficit and surplus, it’s one in which we have a definite surplus. One can feel the collective shudder from the economic nationalists, but these are facts that can only be changed with economically suboptimal government interventions.

Greater productivity means fewer people are needed to produce a given amount of goods. That is undeniably a positive development. Productivity improvements are why the number of manufacturing jobs has fallen from its late-1970s peak:

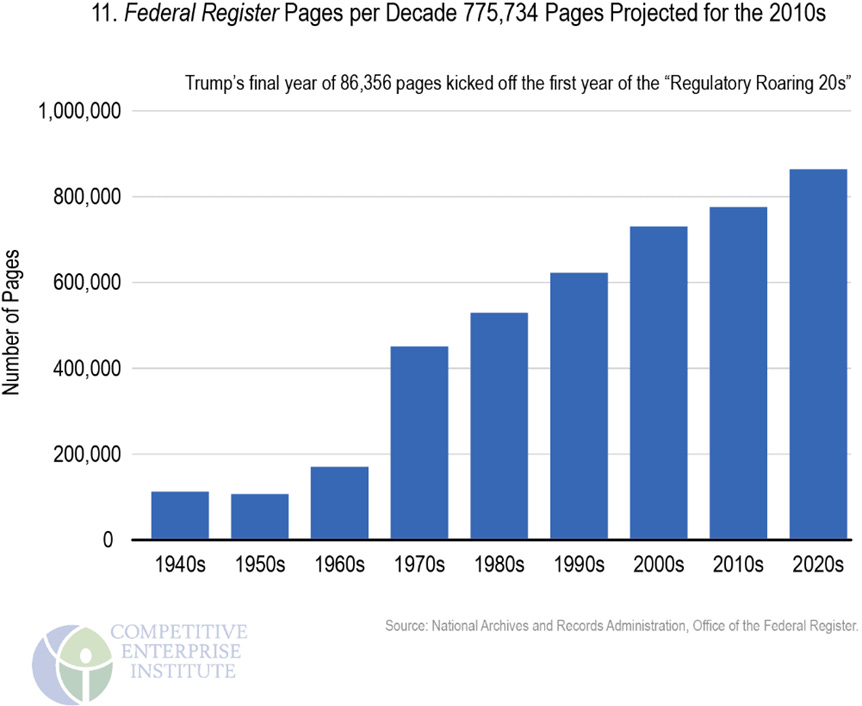

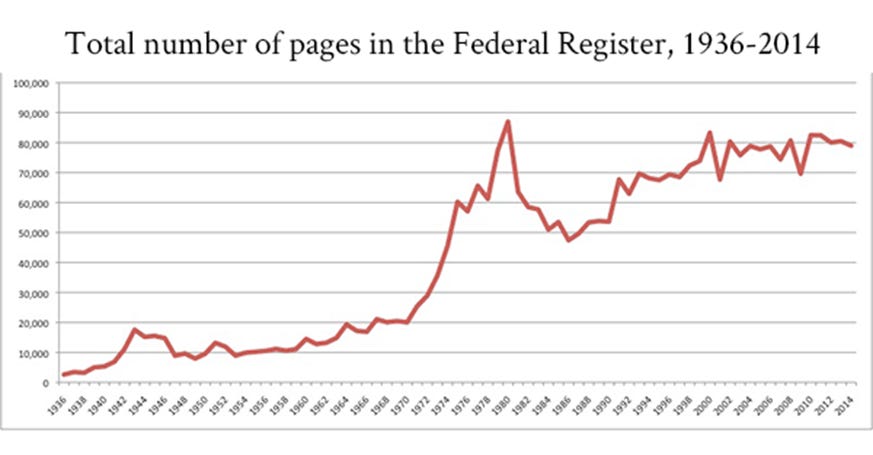

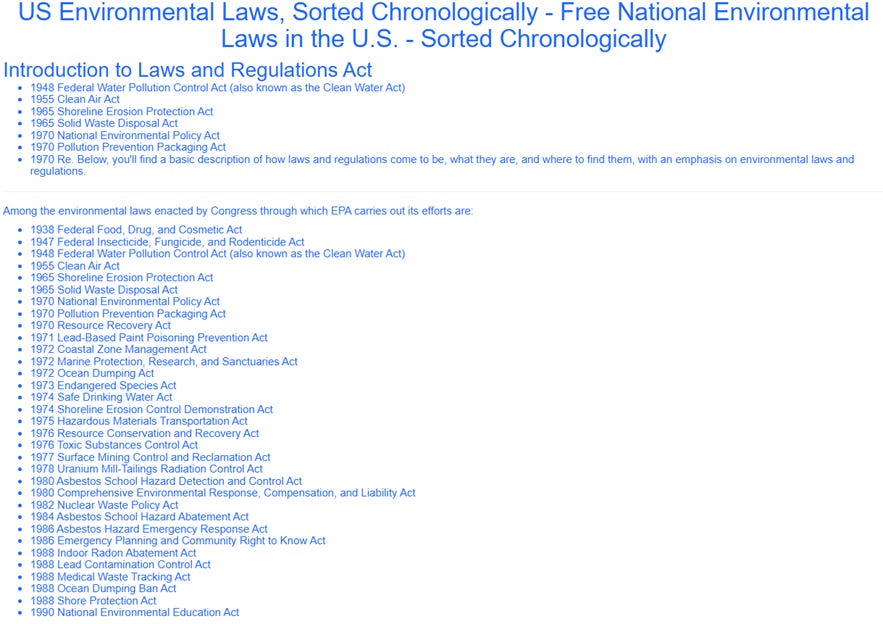

Those job losses did indeed hollow out the economies of the Rust Belt states, but that did not have to happen. Although Reinsch does not go into this in his essay, it is important to note here that government regulation ballooned in the 1970s, as did energy prices in the wake of President Nixon’s severing of the final tenuous connection between the dollar and gold, accompanied by a massive increase in environmental regulations, deterioration of the nation’s education system, and gigantic increases in the welfare state. In addition, the nation imported tens of millions of workers, both legally and otherwise.

Source: Ten Thousand Commandments, by Clyde Wayne Crews, 2021

Source: EHSO.com

Those and other government actions increased employers’ costs and reduced American-born workers’ market value. The damage was worst in the places where manufacturing had been strongest, what became the Rust Belt.

If anyone betrayed American workers regularly since the 1960s, it was the U.S. government, and not through free trade but by excessive regulation (especially through environmentalism), currency devaluation, encouragement of expansive immigration, welfare state expansion, and countless other destructive policies. The interventionist style of government that the New Conservatives advocate is what brought on the very destruction of which they now complain.

The New Conservatives want to increase marriage and family formation, reduce immigration, and increase employment in traditional industries. Among those goals, only immigration requires positive government action, and that means managing the border, which President Trump has confirmed to be a surprisingly simple task.

Issues such as employment and family formation are best left to the people themselves, and the key to that is to reduce government involvement to the absolute minimum. Activist government is the problem, not the solution.

If anyone betrayed American workers regularly since the 1960s, it was the U.S. government.

It is positively baffling that we have to remind self-described conservatives about this after so many years of catastrophic government intrusion into every facet of American life. Have they already forgotten the pandemic years and Biden administration? (Eight months ago!)

Governments badgering people to get experimental injections, forcing small businesses to close, forbidding Americans from going to church, arresting people for going to the park, censoring communications, engaging in politicized prosecutions, and lying about absolutely everything—that is what big government did in just the past few years.

The New Conservatives want to go farther in subjecting the family and the American worker to the very entity that has done the most to undermine them by far. That is not conservatism, nor is it sensible. The job of the federal government is to protect our country from invasion, resolve disputes among the states and ensure that they have republican governments, manage relations with other nations, ensure the existence of reliable currency, prevent interstate fraud and criminal violence, and the like. With those things taken care of, Americans are perfectly suited to build things and create families on their own.

The New Conservatives are selling an essentially un-American mindset, a culture of grievance and self-pity that rejects the nation’s fundamental values of independence, hard work, and self-reliance. Reinsch writes,

With data like this, Americans should wonder why they are consistently being misled by leaders on the populist left and right. Such doomsaying about the demise of the working class and the decline of the industrial heartland serves as a dangerous introduction to a politics of grievance, providing a powerful platform to those pushing these views. Our problems in education, family, patriotism, and work rates are undeniable, and many of them Roberts identifies correctly, but rooting them primarily in an economy built on the betrayal and deceit of hard-working Americans is simply false.

The New Conservatives are effective at publicizing the current problems plaguing the United States. They are wrong about the causes and dangerously wrong about the solutions, demanding the very same thing that caused the problems in the first place: government power. Fortunately, their prescription has little public support, Reinsch writes:

… the economic populist program that Roberts and Cass endorse is not endorsed by most GOP voters, who continue to want traditional objectives of economic growth, limited and competent government, low crime, lower prices, and economic opportunity, plus an end to the ideological revolutionary nostrums of the Left.

The New Conservatives’ concern for the American worker and American families is laudable. Their diagnoses of the ills that have befallen vast swaths of the American people over the past century are all wrong, as are their proposed remedies.

“Today’s conservatives in Washington stand on the shoulders of ideas, research, and statesmanship that took decades to build. They would do well to improve it, not denigrate it,” Reinsch writes.

The American right has always manifested sympathy for ordinary, hardworking people and advocated policies that free Americans to build, create, and enjoy the fruits of their investments of time, labor, and money. The New Conservatives want to rebuild the nation’s families, economy, and culture. The free-market right knows the way to do this. The American Way.