Crime Stats Are Missing the Mark

Increases in the average time between the reporting of crimes and the arrival of police are aggravating the underreporting of crimes—and the resulting inaccuracy of govt. crime statistics.

Writing in the New York Post, Manhattan Institute researcher Rafael A. Mangual reports NYC police are taking longer to respond to reports of crimes. In addition to putting individuals in greater jeopardy, this slowing of response times “will likely contribute to the already significant problem of underreporting — particularly [of] property offenses” and “will likely impact clearance rates—the share of reported crimes resulting in an arrest—which have fallen significantly in New York City since 2020.”

The wait times for help have increased significantly in the past six years, and the effects on attention to serious and non-critical crimes (as opposed to “critical” crimes) are especially pronounced, Mangual writes:

Compared to January 2018, NYPD response times reported in December 2023 have risen across the board—that is, for critical (up 22%), serious (up 45.5%), and non-critical (up 28.7%) calls.

The average wait time for the latter—noise complaints, loiterers, and the like—is now more than 27 minutes.

People are now waiting nearly a half-hour for the police to arrive to deal with the latter offenses.

The obvious cause of this slowing of police response is the drop in the number of officers on the streets, Mangual notes:

The NYPD has gone from a force of approximately 36,000 uniformed personnel in 2018 to just over 33,600 today—a reduction of nearly 7%.

That may seem manageable, but the impact of losing approximately 2,400 cops on response times is significant, especially since [the] number of calls for service has skyrocketed.

Unfortunately, Mangual says, the prospects of the city government replacing those officers are basically nil. The lawmakers certainly have done nothing useful about it thus far.

Ironically, this lack of policing may make the statistics indicate that things are getting better when they are in fact becoming much worse. The slower the police are in responding to crimes, the less likely people are to bother to report offenses against them, Mangual reports: “Using a unique data set from Manchester, England,” a 2017 study published in the Review of Economic Studies “found that ‘a 10% increase in response time leads to a 4.6 percentage points decrease in the likelihood of clearing the crime.’”

Ironically, this lack of policing may make the statistics indicate that things are getting better when they are in fact becoming much worse.

The slowing of police response times is bound to push crime rates up further and further reduce the quality of life in New York City. With police being called out to fewer crimes and apprehending fewer of the perpetrators of that smaller number of (reported) offenses, more offenders will be left out on the streets to terrorize the city’s residents, workers, and visitors.

Meanwhile, crime statistics will look better even as the situation for the average person becomes progressively worse.

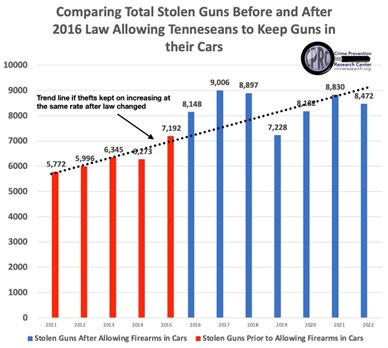

An instructive variation on this phenomenon occurred in Tennessee starting in 2013 after the state passed a law allowing people to store firearms in locked vehicles. A Nashville TV station reported on January 30 that whereas “there were just 46 guns reported stolen from motor vehicles for the entire state of Tennessee” in 2013, that number “shot up” (their words) to more than 2,000 reported cases in 2016 and 5,400 in 2022. The paper blamed the law for a rapid increase in firearms crimes during that period.

The key in the TV report is the words “guns reported stolen,” specifically the word “stolen.” It’s easy to hear that phrase as “guns stolen” and forget that the two things are very different. As the Crime Prevention Research Center (CPRC) notes, legalizing the storing of guns in cars gives firearms owners a vastly greater incentive to report those crimes; because, of course, telling the police about the theft of a firearm from your vehicle used to involve incriminating yourself in the crime of leaving a gun in your car:

The numbers from News Channel 5 are very attention-getting, with a massive 43- to 117-fold increase in the theft of guns from vehicles, but there is a big problem with measuring the number of guns stolen from vehicles. Presumably, if it was illegal for you to have a gun in your car, much of the increase in reports of guns stolen from vehicles might only be because people were then willing to report guns stolen that way once it was legal to do so starting in 2016.

CPRC notes that the number of people with permits for concealed handguns more than doubled in Tennessee between 2011 and 2022 and the rate of reported firearm thefts from vehicles decreased from 16.93 percent in 2011 to 11.58 percent in 2022.

The CPRC notes that “the total number of stolen guns was increasing before the law went into effect” and “if the total number of stolen guns wasn’t affected by the 2016 law, it would be hard to blame the law for any changes in crime committed with stolen guns.” (The discrepancy between the TV station’s use of 2013 and CPRC’s use of 2016 as the measuring stick is based on the passage of two different state laws, with the 2016 revision having a much greater effect than the initial law.)

Such distorting effects on the public’s reporting of crimes are surely happening in other cities as well.

As the situation in New York City illustrates, the progressive increase in underreporting of crimes will create a widening gap between the reality on the streets and what the statistics show. Politicians and the media will cite crime numbers to claim things are better than they are, and the gap between what people experience in the city and what the authorities and the media say is happening will further undermine the authority of the city government and the press—though of course there is not much farther the public’s opinions of those establishments can fall.

As the situation in New York City illustrates, the progressive increase in underreporting of crimes will create a widening gap between the reality on the streets and what the statistics show. Politicians and the media will cite crime numbers to claim things are better than they are….

Meanwhile, the quality of life in New York City and other soft-on-crime communities will continue to decline, with those foolish policies now buttressed by increasingly erroneous statistics.

Sources: The New York Times; Crime Prevention Research Center