Celebrating Charlie Chan's 100th Birthday

A great American character was introduced 100 years ago today.

Here’s a little change of pace—but not of aim—for this site. Much of my writing over the years has been on cultural issues, on films, books, television, music, manners, and so on. One subject on which I’ve written multiple times is the fictional detective Charlie Chan. Chan is a Hawaiian-born police detective who appeared in six mystery novels by author Earl Derr Biggers, beginning in 1925, and in numerous movies, radio shows, and other media products.

Chan is a brilliant detective who speaks with rather limited proficiency in English, and is portly, exceedingly well-mannered, honorable, and of sterling personal character. Biggers, who wrote several other very entertaining mysteries and countless other stories and books, based Chan on two Honolulu detectives he read about in a newspaper: Chang Apana and Lee Fook.

Biggers was inspired to create the character as an answer to the “Yellow Peril” villains often depicted in early twentieth century British and American mystery and suspense stories, such as the insidious Dr. Fu Manchu. “Sinister and wicked Chinese are old stuff, but an amiable Chinese on the side of law and order has never been used," Biggers wrote in 1931.

Today marks the centenary of Charlie Chan’s first appearance in print, on January, 24, 1925 in the novel The House Without a Key. The book is a good, entertaining mysery with interesting and believable characters. Chan is a rather minor character in this one, and he became the star of the series thereafter.

Charlie Chan became a very popular character in the movies, so much so that the Chan films were instrumental in keeping the Fox studio afloat in the 1930s. There have been 49 films featuring Charlie Chan thus far (none since 1981), according to IMDB.com.

Up through the the 1970s or so, American film critics generally recognized the Chan films of the 1930s to the mid-1940s as having been very good (with the quality declining thereafter as the series was dropped by Fox and picked up by the low-budget Monogram Studios), and the character of Charlie as a very positive depiction of an unusual detective despite his minor foibles of limited English profiency and use of sometimes corny aphorisms.

As ethnic divisions increased in the United States in the last quarter of the twentieth century, activists frequently picked on Chan as representing a superior attitude of white Americans toward Asians. In reaction, the corporation that owned the rights to the best Charlie Chan films, the Fox series, have treated both Chan and their customers very shabbily since the 1990s, as I wrote about here and here in defense of Charlie Chan. I think that it is obvious that Charlie Chan is a well-conceived, mythical-level literary character whom people of any ethnicity should admire.

Interestingly, one outlet that has presented defenders of Charlie Chan is public radio and public television. NPR gave a defense of the character on its program Fresh Air and published an article making the case that Americans should give Charlie Chan “a second chance” in 2010, and PBS Newshour praised the American Movie Classics cable channel in 1998 for presenting a Charlie Chan movie marathon.

To celebrate the 100th anniversary of Charlie Chan, I’m reprinting here a piece I wrote in 2001 for The Weekly Standard. I hope that you will enjoy it and share it widely, to help set the record straight on this great American character.

CRITICS HAVE NEVER cared much for Charlie Chan, but the portly Chinese-American detective has been a favorite for three-quarters of a century. Detective-Sergeant Charlie Chan of the Honolulu police became a globally recognized figure through the [six] novels Earl Derr Biggers published between 1925 and 1932. Numerous films featuring Chan quickly followed. He was featured in a radio series from 1932 to 1948 and a television series starring J. Carol Naish–to say nothing of a comic strip, a short-lived mystery magazine in the 1970s, and even an animated television series for children.

When Biggers conceived “The House Without a Key,” the first of his Chan stories, he wanted a new kind of investigator. Born in Ohio and educated at Harvard, Biggers had achieved success as the author of conventional romantic melodramas featuring a dollop of mystery, his most popular being the novel “Seven Keys to Baldpate” (1913), which George M. Cohan adapted into a popular Broadway play. Biggers noticed that mystery writers had created Sherlock Holmesian “master detectives” of nearly every stripe–except one. “Sinister and wicked Chinese are old stuff,” he remarked, referring to Sax Rohmer’s Dr. Fu Manchu novels and countless imitations, all using Asians as stock villains. “But an amiable Chinese on the side of law and order had never been used.” So Biggers simply reversed the stock characteristics, replacing villain with hero, evil with good, arrogance with humility, greed with generosity, power-lust with serenity, ostentation with modesty, and brutality with courtesy.

Biggers seems not to have realized how popular such a simple reversal of characterization would prove. In “The House Without a Key,” he does not even introduce Chan until more than a quarter of the book has passed, and even then the hero does not appear at all formidable: “He was very fat indeed, yet he walked with the light dainty step of a woman. His cheeks were as chubby as a baby’s, his skin ivory tinted, his black hair close-cropped, his amber eyes slanting. As he passed…he bowed with a courtesy encountered all too rarely in a work-a-day world, then moved on.”

Described by another character as the best detective on the Honolulu police force (which may not be intended as a particularly strong endorsement), Chan is first seen in action in a humble posture typical of his character in all the years since: “The huge Chinese man knelt, a grotesque figure, by a table. He rose laboriously as they entered. ‘Find the knife, Charlie?’ the captain asked. Chan shook his head. ‘No knife are present in neighborhood of crime.'”

Biggers plays Chan against the Great Detective stereotype by introducing his hero with a failure, his inability to find the murder weapon. But Chan proceeds to solve a complex mystery of murder among wealthy transplanted Bostonians, and all the important facets of his character are present from the start. In his first conversation, Chan offers one of his trademark aphorisms: “The fates are busy, and man may do much to assist.” He is unassuming but intelligent, perceptive, and direct: “Humbly asking pardon to mention it. I detect in your eyes slight flame of hostility. Quench it, if you will be so kind.” He is always polite: “Mere words can not express my unlimitable delight in meeting a representative of the ancient civilization of Boston.”

In the novels, Chan tends not to dominate scenes in which he appears, and he is almost preternaturally calm and equable. No great physical specimen, Chan is a middle-aged family man. He speaks in a “high, sing-song voice,” and, as befits a man whose first language is Chinese, his grasp of English is somewhat tenuous, though often rather poetic: “Story are now completely extracted like aching tooth.”

Despite his travails with English syntax, Chan is not ignorant. He knows the islands and their inhabitants. Like Sherlock Holmes, he can tell the difference between tobaccos. Red clay on a car’s accelerator pedal, a fresh bullet hole hidden behind a recently moved picture, a murdered parrot, a stolen antique pistol: “All the more honor for us,” he says in “The Chinese Parrot,” “if we unravel [the mystery] from such puny clues.”

Biggers’s Charlie Chan novels are neither psychologically complex works nor models of literary style, but they are pleasant romances with a smattering of social criticism and a good deal of common sense. And Chan is an original and interesting character. But he is best known from his numerous film appearances. Pathe first brought him to the screen in 1925 in a serial of “The House Without a Key,” but it was only in the 1931 Fox film “Charlie Chan Carries On” that the real Chan emerged. The detective did not appear until near the end of the film, yet audiences responded very positively to Swedish-born Warner Oland’s portrayal, especially the character’s pithy aphorisms such as “Only a very brave mouse will make its nest in a cat’s ear.” (Oland, interestingly enough, had just finished portraying the evil Dr. Fu Manchu in three films for Paramount.)

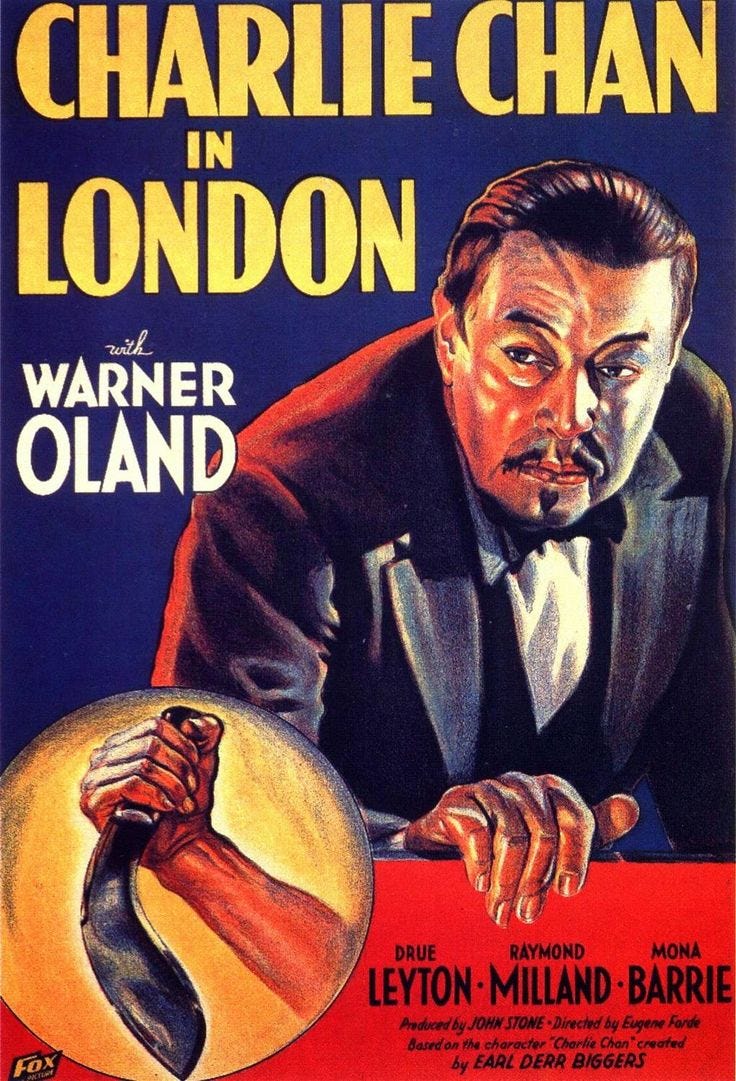

Fox quickly purchased the rights to “The Black Camel,” the fourth Chan novel, moving the detective to the center of the story and teaming Oland’s Chan with a sinister psychic played by Bela Lugosi in a story concerning the murder of a movie star. But it was not until several films later, in 1934, that the series really took off, when Fox assigned John Stone as associate producer and the studio ran out of Biggers novels to adapt. Stone came up with the idea of setting the stories in interesting locations around the world, beginning with “Charlie Chan in London” (1934), and he introduced comic relief in the form of Keye Luke as Number One Son, Lee Chan, in “Charlie Chan in Paris” (1935). Stone also strengthened the main character by reducing Chan’s use of aphorisms (and giving him better ones to say), decreased the love-story element, and established the convention of Chan gathering the suspects near the end of the film for a reconstruction of the crime and identification of the killer.

The budgets were quite serviceable for a B picture series, with such supporting performers as Ray Milland and Boris Karloff. The investment paid off: Costing between $250,000 and $275,000, the films made more than a million dollars apiece. After Oland’s death, in 1938, Fox assigned Sidney Toler to the role. Toler was not nearly as good an actor, and his Chan is not as placid and charming as his predecessor’s. But Toler’s character was more formidable: taller and more vocally expressive and physically agile than his predecessor. Toler also brought out more of Chan’s humor, to good effect.

To ensure the series didn’t decline in popularity, Stone made sure to create especially suspenseful and unusual story lines. “Charlie Chan at Treasure Island” (1939) is in fact one of the best of the series, with Cesar Romero in an excellent performance as the Great Rhadini, a debunker of phony psychics. Within three years, however, the series was in decline, in part because of a loss of inspiration after the grueling pace of three films per year, but also because of the wartime contraction of international markets. The series moved to the very-low-budget Monogram Studios, and when Toler died, in 1947, he was replaced by Roland Winters. The Monogram films are widely reviled by critics for their absurd plots and abundance of low humor, but they did well for such low-budget fare, and the series lasted until 1949.

In his best films, Charlie is an almost ideal human being: wise, calm, observant, humble, polite, patient, affectionate, and generous, but also, when necessary, crafty, devious, and merciless. He frequently uses subterfuge to trick the killer into revealing guilt, as in “Charlie Chan at the Circus,” where he sets up a fake operation on an injured circus performer to lure the murderer into trying to finish the job. Comedy helps the films avoid sappiness. Near the beginning of “Charlie Chan in Egypt,” we see the great detective awkwardly riding a donkey and unceremoniously falling off. In “Charlie Chan at the Wax Museum” (1940), Jimmy Chan, mistaking his father for a wax figure, kicks Charlie in the backside.

As befits a successful police detective, Chan is highly observant. When he walks into a bank in “Charlie Chan in Paris,” his eyes rove as if by long-ingrained habit, examining everything, and he even checks his watch against the bank’s clock. “You’ve certainly got an eye for detail,” says a man helping him, to which Chan sagely replies, “Grain of sand in eye can hide mountain.” He is adept with the use of technology, saying, “Good tools shorten labor,” in “Charlie Chan at the Circus,” but he is not overly dependent on it. His detection techniques blend both ancient and modern ways of thinking, a major theme of one of the best of the films, “Charlie Chan in Egypt.”

Also of great value is Chan’s remarkable patience. He always takes his time in following the evidence and deducing its meaning, while the other policemen and Charlie’s well-meaning sons inevitably rush about trying to do everything too quickly, jumping to absurd conclusions. “Theory like mist on eyeglasses–obscures facts,” he says in “Charlie Chan in Egypt.” In “Charlie Chan at the Wax Museum,” he says, “Suspicion is only toy of fools.”

This composure clearly flows from the character’s great humility. When a dignitary raises a toast to him in “Charlie Chan in London,” saying, “To the greatest detective in the world!” Chan demurs: “Not very good detective, just lucky old Chinaman.” A British policeman repeatedly calls him Chang, but Chan seems to take no notice of it. Such selflessness affords him an extraordinary but undemonstrative courage. In “Charlie Chan at the Circus,” Lee says, “It’s kind of creepy here in [the murder victim’s] room,” to which his father replies, “Then recommend you brush teeth, say prayers, and go to bed.” After an attempt on his life, Chan tells Lee that they can go back to sleep: “Enemy who misses mark, like serpent, must coil to strike again.”

Chan’s humility also makes him a model for the virtues of bourgeois conventionality and self-control. Short and plump, soft-spoken, always well-groomed but never ostentatious, Chan wears simple dark suits or plain white suits befitting his tropical home. Also highly conventional is Chan’s attitude toward sexual morality. He is a loving family man, with eleven children in the first book and thirteen later–at a time when the American birth rate was dropping rapidly. He keeps photos of his children on his dresser when traveling. Moreover, those of his children who are not blundering about in trying to help him solve cases are quite well-behaved. In “Charlie Chan at the Circus,” they all come running when Lee blows a whistle, even though they’d obviously much rather watch the show.

The importance of Chan’s personal life is explored in “Charlie Chan at the Olympics” (1937), when a gang of spies kidnaps Charlie’s son Lee to force the detective to turn over a newly invented radio-controlled plane. Charlie is devastated, which Oland shows especially well through his dejected posture and body movements. (By this time, the actor’s mind was seriously deteriorating because of alcoholism, but his tranquil mien made the character seem even more serene and charming.) The anxious parent does not overcome the great detective, and Charlie cleverly manages to retrieve his son without giving up the plane. “You’re a fine officer,” says an associate. “You went through with your duty even though it meant risking your son’s life.” Charlie calmly responds: “Better to lose life than to lose face.”

In each Charlie Chan film, order and peace are disrupted by ambition. Chan, representative of all that is humble, decent, good-natured, and conventional, investigates the crime and discovers the perpetrators, who are almost always motivated by a desire for more good fortune than society and circumstance allow them to obtain morally and legitimately. Gamblers, spies, Nazis, saboteurs, thieves, forgers, embezzlers, grave robbers, occultists, smugglers, drug runners, jealous lovers, greedy relatives: these are the villains in the Chan stories, and they are victims of their own disdain for others. In Charlie Chan’s world, people turn to crime not because of deprivation but because they see themselves as more deserving than others. Chan sees to it that these individuals are expelled and order is restored.

Hence, ironically for a man of Chinese descent, Chan not only works to strengthen the Western, Christian, bourgeois moral order but, perhaps equally important, he exemplifies it. The use of non-Chinese actors to play Chan has caused controversy in recent years, but the films’ upholding of Western values may be the real reason multiculturalists so despise them. Actually, the films seldom take explicit notice of Chan’s ethnicity, and in the few instances when someone other than Charlie himself does so, it is presented as very bad form. In “Charlie Chan at the Opera,” for example, the low-class Inspector Nelson (William Demarest) refers to Chan as “Chop Suey” and says, “No Chinese cop is gonna show me up!” In “Charlie Chan on Broadway,” the same policeman (now played by Harold Huber) suggests that a band play “Chinatown, My Chinatown” to greet Chan, but a nearby reporter says, “You’ll have to excuse the Inspector’s broken English–he’s a Brooklyn immigrant.”

Charlie Chan’s new, real-life enemies among his multiculturalist critics represent forces similar to those he has always fought: people who despise the bourgeois social and moral order because they consider themselves better than the sheep who accept it. Given Chan’s past history, however, the odds are strong that the great detective will triumph over them, too, and serve future generations as a figure at once entertaining and edifying.

Thank you. I think we miss something in forgetting or canceling these characters. It's kind of funny when Proper White Liberals opine about northeast Asian people; they sometimes forget that those cultures have a lot of social order and tradition, and respect for certain old-fashioned parts of their host cultures. Probably why Orientals (to invoke a location and period in history) were so well-assimilated as subcultures in the West.

The character of Charlie Chan really was somewhat of an ambassador in the entertainment space.

Thank you for introducing me to this interesting character. Just got the series on Kindle, thanks to you.