A Strong Historical Case for Nullification of Federal Laws

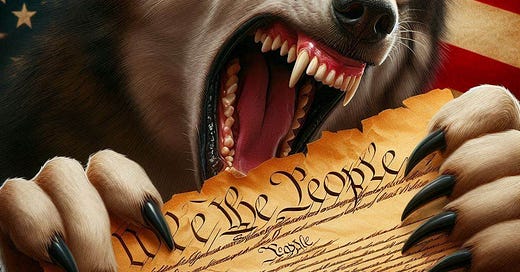

The intensive centralization of the U.S. government has been unconstitutional. A myth about federal supremacy has been central to that "fundamental transformation" of America.

As I have mentioned in the past, the U.S. Constitution has multiple built-in protections against the accumulation of excessive power in the central government:

[E]ach branch has veto power over actions by the federal government. Under the Constitution, the federal government is not to be allowed to do anything unless all three branches agree that the proposed law is in accord with the Constitution.

Thus, soon after the ratification of the document, the Supreme Court asserted its authority to interpret whether federal laws were justified under the Constitution. The president likewise was given this authority—and more importantly, the responsibility—to halt unconstitutional actions by Congress, made explicit in the existence of the presidential veto.

If the federal government follows the Constitution in both word and spirit, most government authority is left to the states and the people (Article 1, Sections 8 and 9 and Bill of Rights, especially Amendments 9 and 10).

Unfortunately, I noted, the states’ “authority to judge the constitutionality of national laws was not given clear protection by the Constitution and has long been derided as nullification.” That has allowed the national goernment to operate on the premise that it itself has sole authority to decide what it is constitutionally allowed to do, which has been the presumption for a quarter of a millennium now.

The result has been greater and greater accumulation of power in the central government, with disastrous results. The federal government has been running up increasingly unsustainable debts, interference in other countries’ affairs has killed or wounded millions of Americans, the federal welfare state has destroyed tens of millions of families, excessive regulation and high tax rates combined with government favoritism toward special interests have grossly distorted the economy, censorship is on the rise, the laws are being used to turn political enemies into political prisoners, and countless other harms have been inflicted by the massive control center in Washington, D.C.

This does not have to be the case.

Although states’ nullification of federal laws has been anathema since the early days of the republic, the Constitution by its very nature and its wording not only allows it but insists on it.

In an ongoing discussion at Law and Liberty, Mises Institute Senior Fellow Tom Woods points out that the dispute over the constitutionality of state nullification of federal laws is based on the premise that the states handed over all their sovereignty to the national government when they ratified the Constitution, and that the states’ authority is subordinate to that of the feds:

The root of our disagreement goes back to the competing theories of the Union—the nationalist theory, whereby the United States is and always was a single, indivisible whole, with spokesmen like Daniel Webster and Joseph Story, and the compact theory of the Union as a collection of states with liberties of their own that preceded the Union, with proponents like Thomas Jefferson and Abel Upshur—that have defined American history.

A big flaw in the anti-nullification argument is the lack of historical support for the nationalist theory among the founders, writes Woods: “As I lay out in my book, I have found no systematic rendition of the nationalist theory anywhere until the 1830s, but ample descriptions of the compact theory (historian Brion McClanahan rightly calls it the compact fact) throughout the 1790s,” Woods writes.

The nation’s founders, Woods notes, “created something very different from the consolidated nation that grew out of the French Revolution and that came to dominate the Western political landscape.”

This dispute is of great importance because the argument against nullification relies heavily on the Constitution’s Supremacy Clause: “This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.”

If the federal government is ultimately sovereign, the states are indeed subordinate. That is not the case, however, and never has been. Woods writes,

In the American system no government is sovereign, not the federal government and not the states. The peoples of the states are the sovereigns, and their ratification conventions are the expression of their highest sovereign voice. It is they who apportion powers between themselves, their state governments, and the federal government. In doing so, they are not impairing their sovereignty in any way. To the contrary, they are exercising it.

The Ninth and Tenth Amendments to the Constitution clearly confirm this:

Ninth Amendment: The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.

Tenth Amendment: The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

The Constitution and Bill of Rights establish a central government with limited, enumerated powers and does not transfer sovereignty from the people to either the national government or the states. It would have been foolish for the states to create an all-powerful central government, and they did nothing of the kind, Woods notes:

It would seem prima facie unlikely that the states would have ratified a Constitution with a Supremacy Clause that said, in effect, “This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in pursuance thereof, plus any old laws we may choose to pass, whether constitutional or not, shall be the supreme law of the land.”

Although lawmakers and courts have long assumed that the nationalist theory is true, especially based on the arguments of pioneering Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall, the historical documents and debates say otherwise, Woods writes:

My co-author and Madison and Jefferson biographer Kevin Gutzman, whom I mentioned above, has the benefit of a PhD in history from the University of Virginia as well as a law degree. It is from that vantage point that Kevin is able to warn people: “Never confuse ‘constitutional law’ with the Constitution.” “Constitutional law” is what they teach in law schools, where even right-of-center students have their brains colonized by the evidence-free nationalist theory of the Union. Students learn a bunch of famous cases rather than the Constitution per se. Well, were these cases correctly decided? As Ayn Rand would say, blank out. James Madison said we should look to the state ratifying conventions to find the meaning of the Constitution. Number of John Marshall references to the state ratifying conventions? Zero.

Even Alexander Hamilton, one of the most centralist of the founders, accepted that the Constitution conferred to the federal government only its enumerated powers and did not authorize any actions beyond them, Woods notes:

Alexander Hamilton, at New York’s ratifying convention, said that while on the one hand “acts of the United States … will be absolutely obligatory as to all the proper objects and powers of the general government,” at the same time “the laws of Congress are restricted to a certain sphere, and when they depart from this sphere, they are no longer supreme or binding.” In Federalist #33, Hamilton further noted that the clause “expressly confines this supremacy to laws made pursuant to the Constitution.”

If unconstitutional laws are not binding on the states and the people, then nullification is only a confirmation of what is already true: the laws in question are null and void. By declaring such laws improper, the states would be doing exactly what the Constitution requires.

An additional argument on which anti-nullification people rely is that it would lead to conflict and chaos, with the states defying the federal government willy-nilly and making the execution of valid national laws impossible. Woods quotes Law & Liberty contributor Mark Pulliam as cautioning against nullification for this reason (among others) and arguing that the states and the people should limit their response to attempting to change federal lawmakers’ minds: “Citizens dissatisfied with perceived federal encroachment should resort to the tools of democratic self-government—protests, state and federal political activism, the Article V amendment process, or legal challenges,” Pulliam wrote.

Woods’ reply: “All right, I’ll bite: how’s that been working out?”

The correct answer is “badly and moving toward catastrophically,” in my view.

Given the woeful present state of governance in the republic, Woods counsels that the states and the people give serious consideration to nullification on practical grounds:

I am all for trying whatever might work in a particular situation, and of course nullification is not and cannot be the solution to all our problems. But the burden of proof here belongs on Pulliam, who advocates persisting in the status quo, to demonstrate to me that the same strategies that have failed to restrain the federal government for over a century will, one of these days, suddenly start working.

In Nullification I give my own reasons to doubt that nullification would lead to the kind of chaos that Hobbesians expect. But even if it did, it would be a question of choosing your evil. Which concerns you more: a completely out-of-control regime, or the possibility that some federal laws (let’s face it, almost surely terrible and unconstitutional anyway) go unenforced?

I am more concerned by the out-of-control regime, by far. Anyone who is not a big beneficiary of that regime should feel the same way. Anyone who is a big beneficiary of that regime should take the honorable course and stop accepting its bribes.

Agreement with the long-held but wrong nationalist theory of the U.S. system of government works to the full advantage of leftist centralizers. Thus today it is a conservative attitude in the worst sense of the word. Woods writes,

The enemies of civilization have grown accustomed to seeing us occupy the role of feckless losers, who dutifully play by rules laid down by people who hate us. Nullification is a Jeffersonian tool, and it has deep roots in American history. Without it, we end up with a regime like the one governing us now. So we can play the role of tame, domesticated losers, or we can open that Overton Window nice and wide, and let some fresh Jeffersonian air blow right on in.

The government of the United States is out of control, spending on an unsustainable trajectory while ruining the nation’s economy, crushing individual enterprise, and undermining the character of the people. Further progress down that way will lead to collapse within a matter of a few years. Far from being a threat to the constitutional authority of the federal government, nullification is one of the few courses of action that can help save it from self-destruction.

You and Tom also love prog rock!

A classic case of "great minds"!